A dancer’s journey begins at an early age and ends with a declining body adapted to maturity. It is often said the bravest thing a dancer can do is grow old. They exist in a world where youth is overly prized, and in which the window for a body to maintain its flexibility, power and speed gradually narrows. The body’s deterioration is real for everyone in general, but dancers particularly, better than others, understand and grasp how tiny shifts weaken the greater whole. In the face of reality, oftentimes an older dancer goes through an existential crisis. The need to know what one still has to offer when the body can no longer respond as it once did, is a tune that continuously plays in the mind. Eventually, the performer realizes that what she or he has to offer, in lieu of breathtaking athleticism, are the emotional experiences gained from real life situations. These scenes must be displayed using a vulnerability fit to the audience. The marked shift then changes the perception of the audience from one of awe to one of relating, connecting and thereby eliciting an emotional response from within the spectators attending.

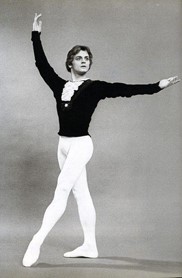

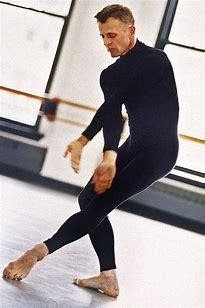

Pictures A & B: The great Mikhail Baryshnikov during his prime. One can see the external bravado that is reminiscent of youth.

Young artists offer unparalleled athleticism. Their bodies are able to withstand forces from different directions, causing stresses and strains without experiencing any adverse pain other than the usual anguish and soreness that wear off quickly. An average dancer’s muscles reach their strongest–peak–level at the age of 25. They are also at their fastest, most flexible and agile. However, considering all of the individual’s strength in youth, the one thing they lack is emotional depth in their characterizations of dance roles. They simply do not have enough real-world experiences to be able to portray storylines accurately with the appropriate vulnerability and emotionality required. Impassioned portrayals lend themselves to externalized, forced effort vs drawing on internal, acquired experiences. This is why one will see budding artists focus their energy on being sharp, controlled, strong, and fast. It is more convenient to work on external biomechanical controls vs displaying internal sensitive susceptibilities. It is rare to find exceptional young performers who need no coaching on how to portray poignant moments. Because of the audience’s incomprehension and lack of background, typically spectators will view the externality–the athleticism and the awe from it–and not be able to understand the potential of depth and layers that can be portrayed for a more well-rounded, relatable and profound experience.

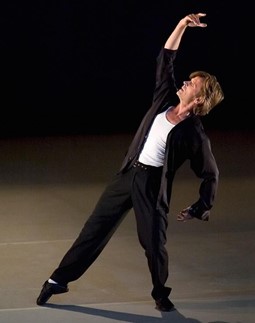

As a dancer ages, in spite of the physical limitations he or she suffers due to abrasion and deterioration, a dancer has gained something valuable: The ability of expression. They have gained personal life experiences through the years; consequently, they can draw upon the sentiments they have felt and use them to appropriately characterize the dance performance. Due to their range of dynamic emotions, older dancers are unparalleled in “telling” a story, in invoking their personal feelings to symbolize drama or fantasy. When movement quality becomes less robust, what emerges in its place is a renewed sense of heroic. Any dancer who has put in decades of training and performing, commensurate with the ability to be still, to shift space and time through presence, is not to be overlooked.

Pictures C, D: Baryshnikov as an older dancer. One can clearly see the internalization of emotion in the body vs the external bravado of his youth.

In a sentence, older dancers are like magicians of stagecraft, whereas younger dancers are uncomfortable with stillness. Always having the need to be in constant movement to perhaps show off their physical talents, it becomes the space they are most comfortable performing in. It takes years to add layers to dances, to be able to weave an unbelievably detailed, beautiful piece that denotes the most harmonious texture. The power of storytelling is what preserves the beauty of an aging dancer. Solomon Dumas has been quoted as saying: “You play the instrument you have and that is what makes the most eloquent music.” In other words, both young and older dancers have a place on the stage; moreover, it is up to the choreographer to extract the best out of every performer and to recognize the existential crisis that eventually could shorten the career of a performer.

BIO: Yasmin Llevada performed with Alvin Ailey in her early years and went on to be a Junior Olympic Dance Champion. She was a dance principle for dance companies such as the former Morka Modern Dance Company and Flamenco Puro before crossing over into American Rhythm ballroom dancing. She has won numerous dance awards throughout her career and has been recognized as an influential choreographer after winning “best musical choreography” at ASM. A coach to some of the best talents in the world, such as premier ballet dancer Alex Wong from So You Think You Can Dance, Ms. Llevada is currently retired from dancing, although sporadically still coaches dance and works as a clinician in the physical therapy field. Presently she’s working towards a Master’s degree in Neuro Cognitive Science, and hopes to study and map the neural signatures of a dancer’s brain.